Countries adopt different policies to control birth rates. Historically, in developing nations, governments often encourage smaller families to speed up growth and industrialization. Fewer children mean less spending on healthcare and education, while more women can enter the workforce — a clear win-win.

At the same time, these policies reflect a deeper challenge first described by Thomas Malthus. He warned that if populations grow faster than resources (mainly food), societies risk shortages and hardship. Managing birth rates helps avoid this imbalance between people and resources, a concern still relevant today.

Anti-Natal Policy

China’s 1979 One-Child Policy is an oft-touted anti-natal example, not only because it was so successful in bringing birth rates down by 85%, but because of its unintended consequences.

As the country prepared to contain birth rates and ease pressure on resources, it enforced strict birth limits, and enforced the policy through a “follow or be punished” system.

Families who complied could receive benefits, while those who had more than one child faced fines, job loss, or even forced sterilization. Women would escape cities they lived in to birth their second, third child, children who essentially fell through the cracks of state welfare, support and even education opportunities.

China’s One-Child Policy – Consequences

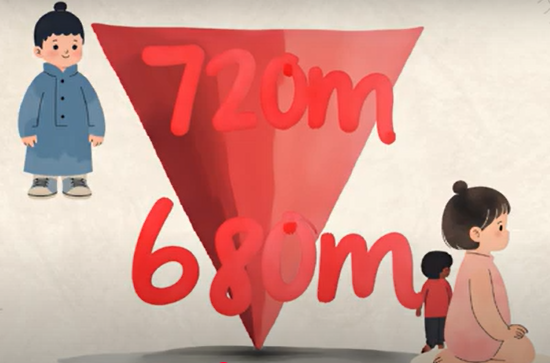

You could say the policy was a success — at least in numbers. Before 1970, the average family had around six children. After the One-Child Policy was enforced, population growth slowed dramatically to just 1%.

It also led to unintended consequences. One was rapid ageing. A 4:2:1 population structure emerged, where one working adult had to support two parents and four grandparents — placing huge pressure on younger generations.

Another major impact was a skewed gender ratio. Due to cultural preference for sons, many families chose to have boys over girls. At its peak, there were 120 males for every 100 females born. In some rural provinces, the rules were relaxed slightly — families were allowed a second child if the first was a girl.

Because many more boys were born than girls, even today, many Chinese men face difficulty finding partners — a lingering effect of the policy.

Pro-Natal Policy

In contrast, Sweden offers a strong pro-natal model. Families receive monthly child allowances from birth until the child turns 18. The country also provides generous parental leave, affordable childcare, and strong work-life balance policies — all designed to make parenting more manageable.

Comparing Statistics

Compared to other developed nations, Sweden’s birth rate at 1.45 does appear relatively high. In contrast, Singapore’s is 0.97 and Japan is 1.2.

Full Population Revision Pack available